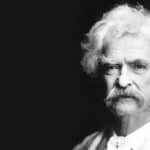

With Mrs. Hemingway by Naomi Wood, the life of Ernest Hemingway is revealed through the eyes of all four of his wives. In The Paris Wife by Paula McLain, Hemingway’s Paris years are laid bare by the narrative of his first wife, Hadley Richardson. In Erika Robuck’s Hemingway’s Girl, the iconic writer’s years in Key West and Cuba, his years with his second wife, Pauline Pfeiffer, are brought to life through the factual inspired young woman, Mariella Bennet.

In an interview with Ms. Robuck, she explained her inspiration for using this character: “While I looked through hundreds of old photos, I came across a photograph of Hemingway on the dock in Havana with a marlin and a crowd of onlookers around him. In the photograph, there were many poor fishermen and a young Cuban girl with an intense gaze. Then I read about a young woman with whom he became infatuated later in his life, and Mariella was born in my imagination.”

Mariella is the catalyst for the story. She is a young woman, just twenty, tethered to life by her mother, bitter and biting from the loss of her husband, Mariella’s father. Mariella too suffers from grief, and yet her mother’s apathy toward life compels Mariella to be a mother to her two younger sisters. From the start, the book reveals her acquaintance with Hemingway. Already she knows of his eccentric personality. When she becomes a maid in the Hemingway household, she becomes acquainted with his second wife, Pauline, once his mistress, and the whole entourage of people that always seem to surround Hemingway. She finds a household in chaos: Hemingway’s two young sons running wild, a cook overwhelmed by panic, and the Hemingways nowhere in sight. What she witnesses most startlingly of all, is the disintegration of a marriage.

Robuck ably reveals Hemingway’s roving eye, his flirtatious proclivity, as well as his unrequited desire for a girl-child, the reason he called so many young women ‘daughter.’ But Mariella fears his libidinous nature will endanger her employment, one she needs desperately to support her family, and yet she finds it hard not to feel the power of his charisma, “Mariella felt his eyes on her as she picked up the last towel and folded it. She heard him walk out the door and down the stairs and was surprised to find that she was holding her breath. She caught sight of herself in the mirror across the room and saw the flush on her skin and knew he’d seen it, too.”

In his dalliance with Mariella, a truth of Hemingway’s character is revealed, the nonchalant, entitled manner in which he used people, to whatever need he had at the time, “(Mariella) couldn’t help but wonder whether she was just an amusement for him—a diversion from boredom or routine. She didn’t like being used, but when he chose to dole out his attention, she knew of none who could refuse. Certainly not herself. She also reasoned that as long as they didn’t cross the line, it couldn’t hurt to play his little game.”

Soon, a young man, a soldier by the name of Gavin Murray, comes into the story. He’s a boxer, and his presence reveals both Mariella and Hemingway’s love of the sport and their enjoyment of gambling on it. At first, the cut-away scenes with Gavin are disruptive, somewhat irrelevant and out of place to the story of Mariella and Hemingway—roadblocks on the intriguing path of the tale. Though through Gavin, Robuck illuminates the terrors of WWI, as well as the after-effects of such a trauma, “It’s an out of body experience…You’re inhuman. You haven’t slept or eaten properly in weeks. You’re soaked to the bone. You’re killing and killing, and crawling over the dead and dying. Your mind is blank. Purely fixed on a target. No emotion. No fear. Until your guys—your close buddies—go down. Then your mind turns on and you can’t think of the target, only of getting them out of there.”

For a goodly length of the book, the more romantic tale tends to dominate the story. Gavin’s interest in Mariella is instant and returned. Their mutual hardships bind them, make them kindred spirits. Mariella soon finds her heart pulled in two directions. Still, the declining scenes with Hemingway lift the book, not only the story but the tone of it as well: from sappy and light, to deeper and more insightful, “It was such a strange thing to be a living, breathing, feeling fly on the wall—in plain view but entirely unnoticed. It made her skin crawl to be a witness to such intimacy and have no connection to it. She derived no voyeuristic pleasure from the scene, only a mixture of emotions that left her unsettled—jealousy, anger, and guilt.”

While there are but a few insights into Ernest Hemingway’s career, when they come, they are crafted deftly, “It was a stark contrast to the noisy, angry days of the previous week, with Papa raging through the house about Scribners, and Cosmo, and his editor, Max Perkins, and being undervalued.”

While the first half of the book seems much more focused on Mariella and her budding romance with Gavin, the second half brings Ernest Hemingway more into the foreground. Once there, the depth of writing rises to the depth of insight, “His physique, his writing his strength—they’re how he defines himself—and when they go away one day, he will have nothing. He alienates too many and relies too much on himself.”

Ernest Hemingway is not the headliner of this tale (which, if he knew it, would be a severe blow to his highly sensitive ego). He is but one in a list of challenges facing young Mariella.

At times, Hemingway’s Girl is more romance novel than anything else, and, unfortunately, those passages tend to be written in a more simplistic, juvenile manner as befitting the subject matter. Far more enduring, far more worthy, are the brilliantly crafted passages with Hemingway; there is found great satisfaction in the work that lies simply in its lovely lyricism, “The sun wasn’t scorching them it warmed them. The wind wasn’t rough; it was brisk. Their hunger didn’t weigh them down it reminded them of the fish they’d fry in a little while. Their poverty was merely simplicity, and living simply was good.”

Hemingway’s Girl is uniquely different from the other recent novels about this enigmatic man. It’s unique perspective and insight, it’s frequent moments of extremely well-crafted prose make it, for the most part, a highly worthy addition.