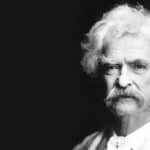

A German philosopher of the 18th century, Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) made significant contributions to the field of philosophy and has had a deep impact on ethics, epistemology, metaphysics, and aesthetics. He remains one of the most influential figures in modern philosophy.

Paul Guyer, Jonathan Nelson Professor of Philosophy at Brown University, is one of the world’s foremost scholars of Immanuel Kant. Guyer has written several books on Kant and Kantian themes and has edited and translated a number of Kant’s works into English. His Kant and The Claims of Knowledge (Cambridge University Press) is widely considered to be one of the most significant works in Kant scholarship.

Simply Charly: You’ve been teaching Kant for years, you’ve written several books about his philosophy, and you even helped edit the Cambridge Companion to Kant. What first attracted you to Kant, and why do you believe he is worth studying?

Paul Guyer: Those may be two different questions! One of the first philosophical texts I studied, in high school, was Hume’s Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding. The brilliance of his arguments dazzled me, above all his critique of our assumption that we have a rational foundation for our belief in the existence of causation in general and our particular causal beliefs. But I really could not believe them. Subsequently, I discovered that another philosopher, Immanuel Kant, had the same response, and had tried to show why belief in causation is a condition of the possibility of any human self-consciousness at all. Naturally, I wanted to understand his response and spent many years trying to figure it out, culminating in my 1987 book, Kant and the Claims of Knowledge.

But what has really kept my interest in Kant alive for over forty years is his philosophy of freedom. I first encountered this idea during a week spent on his later work, Religion Within the Boundaries of Mere Reason, in Stanley Cavell’s great Humanities course when I was a freshman at Harvard. In that work, Kant is trying to reconcile his conviction that the human will is essentially rational with his conviction that the human will is essentially free, and therefore free to be irrational as well as rational, immoral as well as moral. Eventually, I came to believe that Kant’s solution to the metaphysical problem of free will is incredible and the problem itself is problematic, but that Kant’s normative view that the preservation and promotion of human freedom are our most fundamental moral goal is exactly right. Interpreting and defending that normative view has seemed to me a worthy way to spend my own life.

SC: Kant is probably most famous for his Critique of Pure Reason, but he also published several other books and numerous scholarly papers. Which of Kant’s works do you believe are most important?

PG: The Critique of Pure Reason (1781) lays the foundations for Kant’s two further critiques, those of Practical Reason (1788) and The Power of Judgment (1790), which are in turn accompanied by the Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals (1785), the Religion Within the Boundaries of Mere Reason (1793), sometimes referred to as the fourth critique—and two detailed works of application, the Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science (1786) and the Metaphysics of Morals (1797). The latter work is divided into two parts, the “Doctrine of Right” or system of juridically enforceable duties and the state that should enforce them, and the “Doctrine of Virtue,” or system of obligations to ourselves and to others that cannot be juridically enforced but that can be enforced by our own respect for the moral law, self-respect, and respect for others. Even after the last work, when he was well into his seventies, Kant was trying to write a systematic restatement of his entire philosophy, which he could not finish, but the manuscripts for which have come down to us under the name of his Opus Postumum. All of these works are important, and I have worked on all of them, beginning with his aesthetic theory in the Critique of the Power of Judgment, then going on to his theoretical philosophy—epistemology and critique and reconstruction of metaphysics—in the Critique of Pure Reason, and in recent years especially on his writings in moral philosophy. One cannot understand anything in Kant without to some degree understanding all of Kant. But if I could only take a few of his books for a long stay on a deserted island, it would certainly be his works on moral philosophy.

SC: Kant’s moral philosophy was very heavily based on a priori observations or observations based solely on facts other than experience. Why was Kant so insistent on applying a priori principles to moral philosophy?

PG: Kant was convinced that the fundamental principle of morality has to be universally and necessarily true for all rational beings and therefore for all people regardless of their particular desires, upbringing, and so on, and that it can and must be able to be known a priori, independently of the details of any particular person’s experience. But he did not believe that the fundamental principle of morality—in a nutshell, that we should preserve and promote the freedom of all who might be affected by our actions by acting only on “maxims” or policies that all could freely accept, or that are “universalizable”—gives us anything to do apart from the particular desires of human beings, which we can know only from experience. Kant did not think that the a priori, purely rational principle of morality tells us what to do apart from all desires or instead of all desires; it tells us how to regulate our desires, how to choose which ones to act upon, so we may best preserve and promote our own freedom and those of others. Freedom is always Kant’s supreme value, and as he says in his 1784 lectures on “natural right” (political philosophy), reason is only the means to freedom, but freedom is always exercised by acting to realize some desire of someone or other, or in developing means to the realization of desires (“cultivating one’s talents”). Freedom and the moral law are supreme, but second-order values; without actual desires, human beings would have no need to act at all, a fortiori no possibility of acting freely. This is part of the reason Kant was always careful to distinguish human beings from purely rational beings, who, if they existed, would not be agents at all, or human virtue from “holiness of will,” simply not having (empirically given) desires at all.

SC: Kant’s moral philosophy centered around what he called the “Categorical Imperative.” To what exactly did this phrase refer?

PG: The “categorical imperative” is Kant’s term for the fundamental principle of morality as it presents itself to and has to be applied by human beings, who, as I said, are not just rational creatures, but sensible, animal creatures, who have all sorts of desires, some of which will be compatible with morality, while others will not be. The moral law presents itself to us categorically, in the sense that it is binding and allows no exceptions, and it presents itself to us as an imperative, because it will at least sometimes present itself to us as a constraint, bidding us to do something we don’t want to do or demanding that we not do something we would like to do. At the same time, especially in his later works, such as the “Doctrine of Virtue” in the Metaphysics of Morals, Kant makes it clear that our commitment to morality produces feelings of its own, pleasure at the prospect of doing right and satisfaction at the thought of having done right, and that these “moral feelings” or “aesthetic preconditions of the mind’s susceptibility to concepts of duty” can outweigh our feelings of constraint at having to forgo doing something the moral law declares to be immoral act only. On Kant’s view, we can approach psychic harmony between the demands of the moral law and our feelings, and thus lessen the degree to which the categorical imperative feels like a constraint, although, being human, we are not likely to achieve such harmony completely.

The actual content of the categorical imperative is presented by what Allen Wood has called a system of formulations. The first formulation that Kant offers is called the formula of universal law, the requirement that we act only on maxims that could at the same time be universal laws, or be acted upon by everyone else. This will ensure that we are not giving ourselves special privileges, exercising our own freedom in ways that unduly compromise the freedom of others. Then Kant says that the “ground of the possibility” of this formulation of the categorical imperative is a second one, the formula of humanity or the requirement that we always act so as to treat “humanity,” whether in ourselves or others, as an end in itself and never merely as a means. When he eventually defines humanity as simply our capacity to set ends, we see what this means: we must treat our capacity to set ends, which is nothing other than our freedom to determine our own paths and goals in life, as itself our highest end; and acting only on maxims that anyone could freely accept, which is what the formula of universal law requires of us. Finally, Kant says that the first two formulations yield a third, which can be described in both subjective and objective terms: subjectively, acting in accordance with the first two formulas brings us into the state of “autonomy,” the state of acting in accordance with a law that we freely give to ourselves and not in accordance with a mere whim, and, objectively, acting on the first two formulas will bring us toward the condition that Kant calls the “kingdom” or “realm” of ends. In it, the condition in which everyone is treated as an end in him—or herself and therefore the particular ends that each freely sets for him- or herself, in the exercise of his or her humanity as the capacity to set ends, are allowed and promoted by all—to the extent that those ends are themselves compatible with the treatment of others as ends in themselves and the permission or promotion of their ends. The kingdom of ends is not a free-for-all.

SC: How did Kant view religion in regard to morality? Could you define what Kant meant by “moral faith”?

PG: Kant did not believe that truths about anything beyond the possibility of sensory evidence could be established as a matter of theoretical cognition. He held that claims about the existence and nature of God and about the immortality of the human soul could not be established on the basis of any sensory evidence, and therefore lay beyond the limits of theoretical cognition; he even believed this about the fact of the human freedom to choose between right and wrong itself. But he believed that we are entitled to “postulate” or hold as a matter of “practical faith” propositions that are presupposed by the possibility of our being moral, and he held that not only our freedom but also immortality and the existence of God all enjoy this status. His argument for the latter two claims is that morality demands of us to perfect our virtue and to accompany virtue with happiness, either our own virtue with our own happiness or, better, the virtue of all with the happiness of all (this is what Kant calls the “highest good”). Since we do not observe that this happens within our normal lifespans and by our own efforts, he thought we must postulate a “life that is future for us,” in which, with the assistance of God, all this could come about. Or at least so Kant argued in what we might call his “middle period,” of the period of the Critique of Pure Reason and Critique of Practical Reason; by the time he wrote the Critique of the Power of Judgment, the postulate of immortality tends to disappear from his discourse, and in the latest stages of the Opus Postumum Kant suggests that even the idea of God is a projection of our own capacity to be moral, not any kind of guarantee that morality is bound to bring us happiness.

In the 1793 Religion, Kant argues that since humans are sensible as well as rational creatures, we need “aesthetic” or graphic images of the truths of reason, and he interprets the central ideas of Christianity—God the father, God the son, original sin, the possibility of grace—as symbols of the demands of morality, of human freedom, and thus of the possibility of human immorality but also human self-redemption. Kant does argue that the Christian symbols are the best symbols of the demands and possibility of human morality, which I take to be his response to the argument of his great but by 1793 dead contemporary Moses Mendelssohn, who in his own great book Jerusalem of 1783 had responded to demands he prove that Judaism is better than Christianity or else convert to the latter by arguing that although human beings need symbols, for historical reasons different people may be best served by different symbols; therefore, the symbols of Judaism could be as good for the Jews as the symbols of Christianity are for Christians (and, mutatis mutandis, as the symbols of other religions, such as Islam, could be for practitioners of those religions. (In his lightly fictionalized portrait of Mendelssohn in a great play Nathan the Wise, his friend Gotthold Ephraim Lessing had presented Mendelssohn as believing in the equal value of each of the monotheistic or “Abrahamic” religions). I don’t think that either Kant or Mendelssohn succeeded in arguing that all human beings need some religious symbols in order to be moral, but I certainly don’t think that Kant succeeded in proving against Mendelssohn that one religion had better symbols of morality than another.

SC: Kant’s work often addressed the question of Kant’s existence; indeed, this question served as the basis for one of his most famous tracts, The Only Possible Basis for a Demonstration of the Existence of God. What was Kant’s argument for the existence of God?

PG: From Kant’s earliest philosophical publication, in 1755, a Latin academic exercise entitled A New Exposition of the First Principles of Metaphysical Cognition, Kant rejected the “ontological argument” of Anselm and Descartes that the existence of God follows directly from the concept of God as the most perfect being. From that work on he also rejected the standard Enlightenment argument that the existence of God could be inferred from the perfection of his creation, the world, which had already been criticized by Hume in his Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding and, although they would not be published until several decades later, his Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion—but Kant allowed that the existence of God could be proven as the ground of all other possibility rather than actuality. That is the “only possible basis for a demonstration of the existence of God” in the work of that title. By the time he came to write the Critique of Pure Reason, however, Kant rejected that argument too as an idea of pure reason that cannot be confirmed by any sensory observation, and he adopted the position I have already described, that the existence of God has credence only as a postulate of pure practical or moral reason—although he tinkered with the details of that argument for the rest of his life.

SC: Reading Kant’s philosophy, he makes frequent mention of virtue being a sort of moral duty. How did Kant define virtue? What, in his mind, was man’s moral duty?

PG: Kant holds that the moral duty of human being is to preserve and promote the freedom of all, or as he sometimes says the “essential end” of humankind is the “greatest possible use of freedom.” Since freedom is just the capacity to set our own ends, and happiness is nothing other than the realization of our ends or the satisfaction felt in such realization, under ideal circumstances the greatest possible use of freedom would automatically result in the greatest possible happiness of all—the “highest good.” The highest good is thus the supreme or complete object of morality. But since, as we also saw, human beings do not always automatically want to do what they morally should do, they will need strength of will to overcome those of their desires that would stand in the way of their doing what is right. That is what virtue is: “the moral strength of a human being’s will in fulfilling his duty,” as Kant says in the “Doctrine of Virtue.” Virtue is a specifically human necessity—if there were rational beings that never had any desires incompatible with morality, they would not need virtue. But we do have such desires and do need virtue (and do not need to concern ourselves with the question of whether there are any beings who don’t). Kant also argues that virtue is a condition that human beings must and can cultivate and strengthen, though he does not explain exactly how we do this; perhaps his idea is that we prepare ourselves for moments when we are not under moral stress, in the course of our education as well as our maturity, for the inevitable moments when we will be under moral stress.

SC: Did Kant’s philosophy ever change as he grew older, or did his views remain static throughout his life?

PG: As I have been suggesting, Kant’s views underwent constant change throughout his life. The standard view of Kant’s intellectual biography is that there was a great sea-change from the “precritical” Kant of the 1750s and 1760s to the “critical” Kant of the 1780s, which took place during the “silent decade” of the 1770s when he was excogitating and writing the Critique of Pure Reason, but unlike the preceding and succeeding decades published virtually nothing. This sea-change would be marked precisely by the change from the view that the existence of God can be proven by theoretical metaphysics to the view that it can only be a postulate of pure practical reason that we have already discussed. My thought is that the gradual replacement of the view that we must believe in the existence of God even if only on practical grounds to the view that Kant was working out in the Opus Postumum that the idea of God is nothing but an image of our own moral potential is a further development of such significance in Kant’s thought. We should recognize the period from the early 1790s to the end of Kant’s life (he died in 1804, but suffered what was probably a stroke in the fall of 1803 that ended his working days) as a third period of his career. I suppose we would have to call that his “post-critical” period, although to my mind it would properly be called his most critical period.

SC: How did Kant’s view of morality differ from other prominent philosophers such as Locke and Hobbes, or from classical philosophers such as Aristotle?

PG: In a nutshell, the answer is that for Kant the aim of morality is the maximization of human freedom, not human happiness, although (at least under ideal circumstances) maximizing human freedom would also produce the greatest happiness possible for human beings. (Note: the greatest happiness possible for human beings: no amount of human morality can ever remove all the causes of human unhappiness, such as the destruction wrought by hurricanes and volcanoes, but, above all, the unhappiness due to the ineliminable fact of human mortality itself.)

SC: Did Kant ever develop practical applications for his moral philosophy, or was it purely theoretical? Was his philosophy focused completely on the individual, or did he ever apply it to governments or nations?

PG: Kant’s “Doctrine of Virtue” concerns the obligations that individuals have to themselves and to each other which cannot, physically but even more importantly morally, be enforced by the coercive mechanisms of the state, its juridical and penal systems. But his “Doctrine of Right” concerns those of our duties that can and must be publicly enforced, and our duty to be part of a state, but also the limits on what may be enforced by the state—what the Prussian statesman, educator, and linguist Wilhelm von Humboldt, influenced by Kant and a great influence on John Stuart Mill, would subsequently call “the limits of state action.” Kant argued that human beings need the use of and control over external objects—property—to survive, but can only “rightfully”—that is, morally—claim property in circumstances in which they are willing to concede reciprocal rights to others and make such rights secure, which can happen only in a state. Because the human need for property is inescapable—even the most ascetic still need food and sandals—but property can be rightfully claimed only within a state, human beings are, according to Kant, under a moral duty to be members of a state. But, he also argued, a state can, in turn, fulfill its moral responsibilities to its members only if it is a republic, or at least governed on republican principles, and its members are indeed citizens and not merely subjects. By a republic or a state governed by republican principles Kant means a state in which all citizens are equal before the law; in which there is a genuine division of powers among the legislative branch, which represents the sovereignty of the people in the laws it legislates, and the executive and judicial branches, which (together) interpret, apply, and enforce those laws; and in which offices and territory are not held by rulers as private property but are open to all. In his famous pamphlet Towards Perpetual Peace, which has been the object of intensive discussion especially since its bicentennial in 1995, Kant also admonished the crowned rulers of Europe that they would never achieve perpetual peace or a permanent condition of justice by their games of dynastic balance of power, but only by transforming their regimes into republics in which the people who would have to bear the costs of war and not the rulers who have little to lose, would have to vote for war. This was not merely an application of his moral theory to matters of international politics, but a bold and radical statement to make for a professor employed at a state university in the autocratic kingdom of Prussia, one who was already under a royal rescript against publishing anything further on religion, especially in 1795, at a moment when the remaining crowns of Europe were preparing for war against revolutionary France (although by that point France itself was a republic in name only).

Founder of Simply Charly and CEO of Carlini Media, a versatile and fast-growing multimedia company comprising entertainment, design, education, and hospitality divisions.