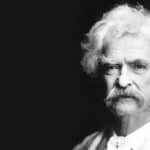

We are deeply saddened by the news of the passing of philosopher and erstwhile Freud critic Frank Cioffi.

We are grateful to Professor Laurence Goldstein for providing us with this full obituary on Cioffi.

Professor Frank Cioffi was born in New York City on January 11, 1928, and died on January 1st, 2011. His forebears came from Vico Equense (Vico’s birthplace) a fishing village near Sorrento. He was the son of Salvatore and Melina Cioffi. He told me the terrible story of how his mother had died giving birth to him and that his father had so adored her that he could not bear to see him, and he was brought up by a great aunt whom he always called his mother and whose son Lou (his uncle) he always regarded as an elder brother. His father died shortly after his mother. I have always thought that this (and perhaps too the mysterious murder of his grandfather in the mid-1930’s) greatly affected his later reflections. He was deeply struck by Schopenhauer’s view that all life is bought at the expense of other life while never accepting Schopenhauer’s metaphysics of pessimism. He also prized Pascal’s reflections on the miseries of human life. Like his admired Santayana he had enjoyed a Catholic upbringing but lost his faith. In Nietzschean moods, I used to tease him that a Catholic is never disburdened of the false myth (as Santayana called it) of original sin. His schooling was in New York City. His ‘brother’ served in the U.S. Army in Europe in World War 2 and Frank at the age of seventeen tried to get into the Marines. He eventually entered the army and was with the occupying forces in Japan. Never the most practical of men and a born intellectual to the core, he told me that he loved his period in the army and was grateful for the opportunity to meet such a diversity of people all of whom he seems to have got on with well. He then had a spell with the graves registration service supervising the repatriation of bodies of servicemen killed in the war from France to the U. S.

He then spent some time in Paris where he attended lectures for foreigners at the Sorbonne and met an old friend from New York, James Baldwin, with whom he discussed the then work in progress Go Tell It On The Mountain. Another friend, Lionel Blue, persuaded Frank to try to get into Oxford helped as he was by finance from the G.I. bill of rights. After a spell at Ruskin College, he entered the newly founded St. Catherines where a friendly Allan Bullock helped him to negotiate his way through the various university requirements. He was tutored in the philosophy part of PPP by Friedrich Waismann and Anthony Quinton. After his degree in 1954, he spent two years researching in Social Psychology at Oxford with Michael Argyle. From 1956 to 1965 he was a lecturer in philosophy at the University of Singapore. When he was asked to resign along with other foreigners in the faculty, the faculty senate passed a resolution deeply regretting his departure. He came to England as one of the founders of the new University of Kent in 1965, and it was there that I met him in 1966. As with other new universities at the time, Kent was inventing new combinations of studies in an attempt to overcome too early specialism. Part One which lasted four terms initially consisted of a course on Britain And The Contemporary World where students had to do a combination of literature, history, and philosophy. Frank Cioffi’s wonderful introductory lectures on philosophy and on the problem of The Meaning Of Life induced many students who did not know the subject to take it in Part Two. His lectures were always meticulously prepared, but like those of the William James and Wittgenstein he so greatly admired were not read but spoken spontaneously. Often they were applauded at the end and where the timetable permitted students asked him to continue. He had a marvelous gift for enlivening his lectures with jokes and anecdotes and historical digressions and references to film and popular culture without ever detracting from their intellectual content and fundamental seriousness. I believe he was called ‘the most amusing philosopher on the circuit.’ When he was offered a professorship and the chance to found a department of his own at the University of Essex a group of teachers and students in the humanities went to the Dean of the Faculty and the Vice Chancellor asking that he be given a professorship at Kent so we would not lose him, but without success. So he went to found an extremely successful philosophy department at Essex. He had been visiting a professor at the University of California at Berkeley from 1970 to 1972 and had spells at Appalachian State University and the Australian National University. After his retirement from Essex in 1994, he came back to live in the house in Canterbury he and his wife Nalini had always loved. He became an Honorary Research Professor at the University of Kent.

Frank Cioffi’s range of reading on his own subject and in literature and history was extraordinary. He defended Oxford analytic philosophy, but he also was acquainted with the world of Franz Brentano, Husserl, and phenomenology. He revered William James and George Santayana and much admired the work of Georg Simmel, particularly the latter’s essay ‘The Nature of Philosophy.’ He himself had highly original things of his own to say, but often did so by way of reflections on the two figures of whom he made a particularly intense study, Wittgenstein and Freud. In 1973, he delivered on the third programme a path-breaking lecture ‘Was Freud A liar?’ which was reprinted in The Listener for 7th February 1974 and then in his wonderful collection Freud And The Question Of Pseudoscience published by Open Court in 1998 and now, sadly, out of print. Cioffi refined his criticism of Freud over the years. He came to feel there had been too much emphasis (partly owing to Popper’s work) on Freud the pseudo-scientist and not enough on Freud the weak humanist. Later critics of Freud such as Frederick Crews, Allen Esterson and Malcolm Macmillan always acknowledged their deep indebtedness to him.

Frank Cioffi’s metier was the public lecture and the essay rather than the organic book. In 1998, his collection of essays on Wittgenstein and related subjects was published by Cambridge University Press under the title Wittgenstein On Freud And Frazer. He was always deeply concerned with what Wittgenstein had to offer the humanities, Wittgenstein on psychology, on aesthetics and music and on religion and in particular with Wittgenstein’s hostility to causal explanation and to scientism, and with Wittgenstein’s preoccupation with solipsism, particularly in the paper ‘‘Congenital Transcendentalism And ‘The Loneliness Which Is The Truth About Things’.’’ The latter phrase is slightly adapted from a thought which occurs to James Ramsay at the beginning of chapter 12 of part 3 of Virginia Woolf’s To The Lighthouse. Cioffi thought that solipsism is often confused with something different (and not nonsensical) an essential community of loneliness which Arnold captured in the line ‘We mortal millions live alone.’

Frank Cioffi was, as the phrase goes, ‘much preoccupied with death.’ He shared Lakin’s view in ‘Aubade’ that there is something specious in Lucretius’ arguments against the fear of annihilation, but he shared the Lucretian view that annihilation is nothing to be feared and could not understand his revered Dr. Johnson’s refusal to accept this. Larkin’s last words ‘I am going to meet the inevitable’ would seem fitting for his final thought.

In the end, he was working on a paper on responses to atrocity, in particular to the Holocaust or Shoah. The following is from a draft. ‘The situation is one in which we anticipate from some future state of epistemic consummation not merely the resolution of our perplexity as to what it is that troubles us, but closure, whereas what keeps the thoughts flowing is not ignorance but ambivalence, and what will put them at peace is not a discovery, but a decision. The guilt of the living towards the dead, for example, needs to be exorcised and not merely acknowledged. As J.C.Powys puts it, ‘You are allowed to forget.’ But his friends and readers will not forget Frank Cioffi as long as they live

‘Not till those grieving die

Will Grief be dead.’

He is survived by his wife Nalini and his step-grandson, Luke.